U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio announced on May 16th, that NATO is close to new guidelines for military spending. Over the next decade, Rubio explained, member states will be expected to expand defense appropriations to 5% of their Gross Domestic Product, or GDP.

Europe is already well underway with preparations for major defense expansion. The obstacle facing most European NATO members is the lack of room in existing government budgets, especially for such a significant expansion as NATO is now pushing for.

As a solution, the political leadership in Europe is charting a new fiscal course: after more than two decades of commitment to balanced budgets, many European countries are warming up to borrowing money for defense appropriations purposes.

Germany announced plans back in March to use budget deficits as a funding mechanism for defense expansion. This is a sharp deviation from the nearly two decades under Angela Merkel’s tenure as chancellor when the federal government vigorously pursued a balanced budget.

The debt-for-defense-minded Germans were joined by Sweden and France, though Paris appears to have reservations regarding the size of new government borrowing.

Even the European Commission is on board with borrowing large amounts of money to pay for Europe’s military expansion. This is perhaps the most significant sign that the political leadership in Europe has collectively determined that the cost and fiscal strains associated with more debt are worth the while when it comes to expanding the continent’s military capabilities.

The NATO-sanctioned defense expansion is shaping up to be a significant experience for Europe’s governments, not only from the perspective of growing military organizations but also from a fiscal viewpoint. Interestingly, it is difficult—to say the least—to find concise, methodical studies of the budgetary fallout of this expansion, in part because many fiscal analysts, like meteorologists, often shy away from long-term forecasts.

At the same time, if Europe’s lawmakers are going to move forward with this major defense expansion, it is essential that both they and their taxpayers/voters know what they are doing. Therefore, to get an idea of the sheer scale of this military spending growth, let us do a little experiment with existing data.

Eurostat, the EU’s own statistics agency, publishes annual updates on member-state government spending. One of their more useful tables is the one that breaks down government outlays by function; the numbers from 2023—the latest Eurostat has published—tell us a great deal about what NATO is pushing its member states toward.

In 2023, the 27 EU member states spent €227 billion on defense. This came out to 1.3% of their total GDP.

If their defense budgets had been at 5% of GDP, they would have spent €860 billion, or €378 per actual €100 in defense outlays.

This is quite an expansion of the defense budget. However, to really get an idea of what it means for the governments across Europe, we should recalculate the defense outlays as a percentage not of GDP, but of total government spending.

For this purpose, let us compare actual defense spending in 2023 to the spending levels needed to meet the 5% of GDP requirement. However, from here on, the numbers reported represent defense spending as share of total government outlays, not GDP.

Again using Eurostat numbers from 2023, we find that Latvia had the highest defense share at 7.2% of their government spending. They stood at the top together with their Baltic neighbors Lithuania (6.8% of total government spending) and Estonia (6.3%), all leaps and bounds above Germany (2.3%) and Austria (1.2%).

To reach the new NATO spending goal, Estonia would have to nearly double its annual defense outlays, from 6.3% of total government outlays to 11%. Germany is going to have to grow its defense outlays 4.5 times, from €46.4 billion to €163 billion. The Spanish government would have to up its military appropriations from €14 billion to €75 billion.

Table 1 compares actual defense spending (in millions of national currency) in 2023 with what it would have to be under the new, pending NATO requirement.

Table 1

In most EU member states, this kind of defense expansion would claim 10% or more of consolidated government outlays. In other words, we can expect budget fights in many European legislatures.

We can also expect investors who buy government debt to raise an eyebrow or two. If the total expansion across the entire EU would amount to well over €600 billion, and if all of that is going to be funded with new debt, then obviously, someone is going to want to buy up that new debt.

Those who consider doing so will carefully scrutinize each government’s debt expansion plan. They will pay close attention to existing debt and the trends in the country’s budget deficits.

This last point is very important. Social media and traditional news outlets have been abuzz recently with more or less harebrained ideas for how to fund Europe’s military expansion. The list includes EU borrowing and then lending to member states—sometimes referred to as ‘front loading’—as well as a scheme where governments let bank customers more or less ‘voluntarily’ convert their deposits to defense bonds.

Wild ideas notwithstanding, Europe’s and NATO’s political frontmen had better come up with a workable funding plan for their defense growth—and do it soon. If they don’t, worries over higher taxes and other options will set the agenda, and public opinion will be swayed accordingly.

By the same token, for every day that Europe does not take appropriate action, investors in sovereign debt will inevitably grow more reluctant to buy new debt from EU member states. It is an open question to what degree this reluctance will spill over to the refinancing of existing debt.

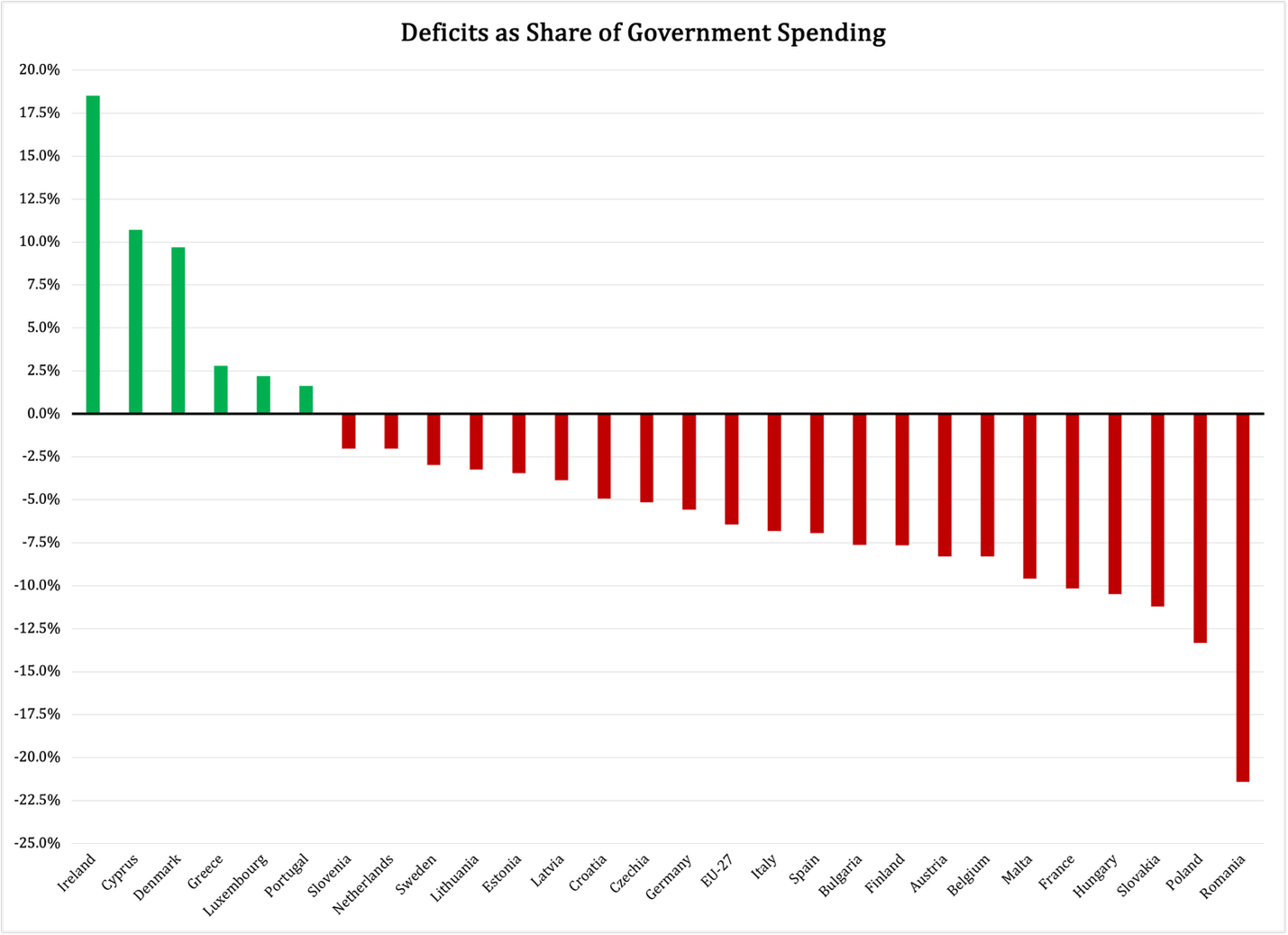

To see why this is not just a hypothetical problem, consider Figures 1 and 2. We start with Figure 1, where the 27 EU states are ranked by order of their budget deficits in 2024. Only six countries—Ireland, Cyprus, Denmark, Greece, Luxembourg, and Portugal—had budget surpluses. The rest had budget deficits that ran anywhere from 2% of government spending (Slovenia, Netherlands) to 20+% in Romania.

Figure 1

With so many member states already in the red, it will be difficult for Europe to attain affordable debt funding for its military expansion. This point is reinforced by the message in Figure 2, which reports the number of years any one of the current 27 EU members has run a deficit in its consolidated government finances.

Since the period from 1995 to 2024 covers 30 years, it made sense to arrange the data so that countries with budget deficits in fewer than half of those years could be marked with a green column. Since Luxembourg has only had six years with deficits, and Denmark ten, they are ranked ‘green’.

Figure 2

The most serious message in Figure 2 is that six member states have had budget deficits every single year since 1995. In fairness, it is important to remember that a long line of deficits only becomes a problem if the borrowed money is spent on welfare state entitlements and similar ‘consumption’ items in the government budget.

If the money is used for public capital formation—the building of infrastructure is a great example—workforce improvement, and attraction of foreign direct investment, then the national economy will inevitably come out stronger. Hungary is a good example.

If, on the other hand, an unending series of budget deficits only leads to the expansion of entitlement programs under the welfare state, then the economy is in great peril. Successful investors in sovereign debt know the difference and will treat Europe’s deeply indebted countries accordingly.

There is no doubt that Europe needs a stronger military. The question is if the way forward goes through more debt or stricter prioritizations in existing government budgets.