When someone falls victim to fraud, the common lament is that the con sounded too good to be true. But for the victims of so-called ‘virtual kidnappings’, it is the opposite; it sounds so terrible that it couldn’t be real.

In the latest case revealed by police in New South Wales this week, a 22-year-old man was convinced by the scammers that he had to take a female high-school student – a complete stranger – into witness protection at his apartment.

The 18-year-old student meanwhile had been conned into believing by the same scammers, who claimed they were Chinese police, that she had to go into hiding with the man at the apartment in the Chatswood area of Sydney.

Police say the two strangers, taken in by the narratives each was fed separately, spent eight days together at the man’s apartment.

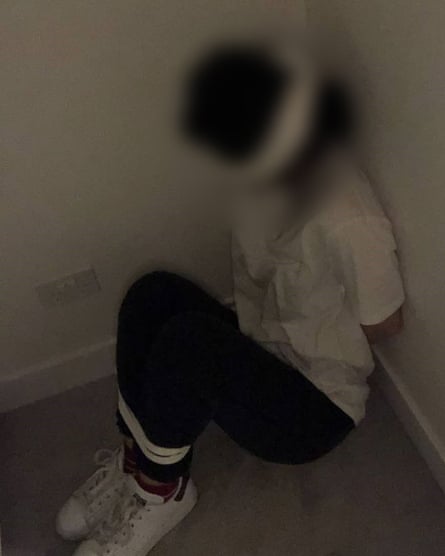

During that time the woman sent a series of photos and videos of herself “kidnapped” to her family via Chinese social media app WeChat.

These messages were followed up by others purporting to be from the Chinese authorities and telling the relatives to transfer money to secure her release.

Police said the woman sent the messages while the man was away from the apartment attending university classes, so he had no idea she was convincing her parents to pay a ransom.

Neither victim were harmed or in danger – indeed when the man left his apartment, she did not try to escape. But that didn’t stop the woman’s parents from paying $213,000 to the scammers via a bank account registered in the Bahamas.

NSW police say the case detected in September is one of nine reported in the state this year, which have resulted in ransoms of almost $3.5m being paid.

They say the 18-year-old woman and 22-year-old man did not even know it was a scam until they were found by police, who were able to track the woman via her mobile phone.

“It appears these scammers are continuing to operate and are once again preying on the vulnerabilities of individuals in the community who are not in direct physical contact with their families,” NSW Detective Chief Superintendent Darren Bennett said in a media release.

“In this incident, police have been told that initial contact was made in July this year after the woman received an email from persons purporting to be Chinese police and claiming her personal details had been illegally used on a package intercepted overseas.

“The individuals behind these ‘virtual kidnapping’ scams continually adapt their scripts and methodology which are designed to take advantage of people’s trust in authorities.”

Billions of dollars are estimated to have been lost globally to virtual kidnappings, which typically target young Chinese adults, including exchange students in Australia.

How the scams work

Scams of this type have been operated for almost 30 years, according to the Monash University criminology lecturer Lennon Chang.

The victim is usually cold-called by the fraudster who, speaking in Mandarin, says that they are from the Chinese government or police.

They are generally told there is an issue with their passport or visa status, or that they are being investigated in relation to a package, before saying they must speak to another official who will confirm further details.

The victim is gradually convinced that the only way to solve the problem is to stage photos of themselves being kidnapped to ensure their relatives pay a ransom.

Scams of this type have been found in North America, Europe and Asia, Chang says.

Police in Victoria, who have also previously reported virtual kidnapping scams, said none had been recorded this year.

“These scams can be aggressive and elaborate, and we understand the callers can be quite threatening, leaving victims feeling frightened and intimidated,” a Victoria police spokeswoman said.

“It’s important that people remember to not comply with instructions to transfer money or supply any personal details.”

According to an Australian Competition and Consumer Commission report published in June, phone calls related to “Chinese authority” frauds were among the top five scams reported to authorities last year. (Scam calls relating to the national broadband network were most common.)

There were almost 1,200 such scams netting $2m reported to the federal government’s Scamwatch website in 2019, the report found – a drop in the number of cases reported in 2018, but an increase in the amount of money stolen.

Senior police spoken to by Guardian Australia say they first noticed cases in the country about five years ago.

But their early investigations were hampered by a concern that raising public awareness could be harmful to the extremely lucrative international student market, and by poor cooperation with Chinese authorities when it came to tracing the money.

Since 2018, police have been more willing to speak publicly about cases in an attempt to educate victims, but prosecutions remain rare; and cooperation from China patchy.

Queensland prosecution

One of few Australian prosecutions occurred in 2015, after police in Queensland raided two properties, including a palatial Morningside home with a swimming pool and a tennis court, and found more than 50 Taiwanese nationals working on the scams inside.

Police alleged the men were being held as slaves, without being paid and after having their passports confiscated. The houses were only found after one of the men broke out and waved down a passing car.

Chang said that in the past decade, since Chinese and Taiwanese authorities cracked down on scammers operating in their jurisdictions, the model uncovered in suburban Brisbane has become common; a large room functioning as a call centre where the various elements of the scam can play out more convincingly because the fraudsters are co-located.

The scams can operate from anywhere with a solid internet connection, he said, but it was rare for them to be established in Australia.

Such rooms have reportedly been found in Spain, Kenya and Indonesia, as well as a host of other countries, Chang says.

In some countries, such as the US, actual kidnappings of exchange students have taken place, undoubtedly making the scams more convincing.

The damage to victims is not just financial. In Australia, there have been multiple instances of the scammers convincing their victims to harm themselves, to make the ransom photos sent to their parents appear more realistic.

Some women scammed in Australia were told they had to expose themselves and take photos, furthering their torment and shame at being caught up in the ruse.

That shame has driven some victims to suicide, according to international reports.

Chang, considered a leading international expert on the scams, says that because of the stigma associated with being a victim of the scam, it is almost certainly underreported.

The scam has been so successful, he says, because it manipulates common fears and beliefs.

He himself has received calls, trying to play along with the scammers long enough to glean information for his research, but they just hung up on him.

Students of his were not so lucky. They told him they had been targeted in such scams, and that their parents had paid ransoms, but they had never reported the offences to authorities.

“They feel stupid,” he says. “They feel: ‘how can you be scammed? How can you believe those people?’ But they were educated, since they were a kid: obey the authorities.”